Guest: The Joy of Working with Floyd Cooper

by Patricia Lee “Patti” Gauch, Floyd’s long-time editor.

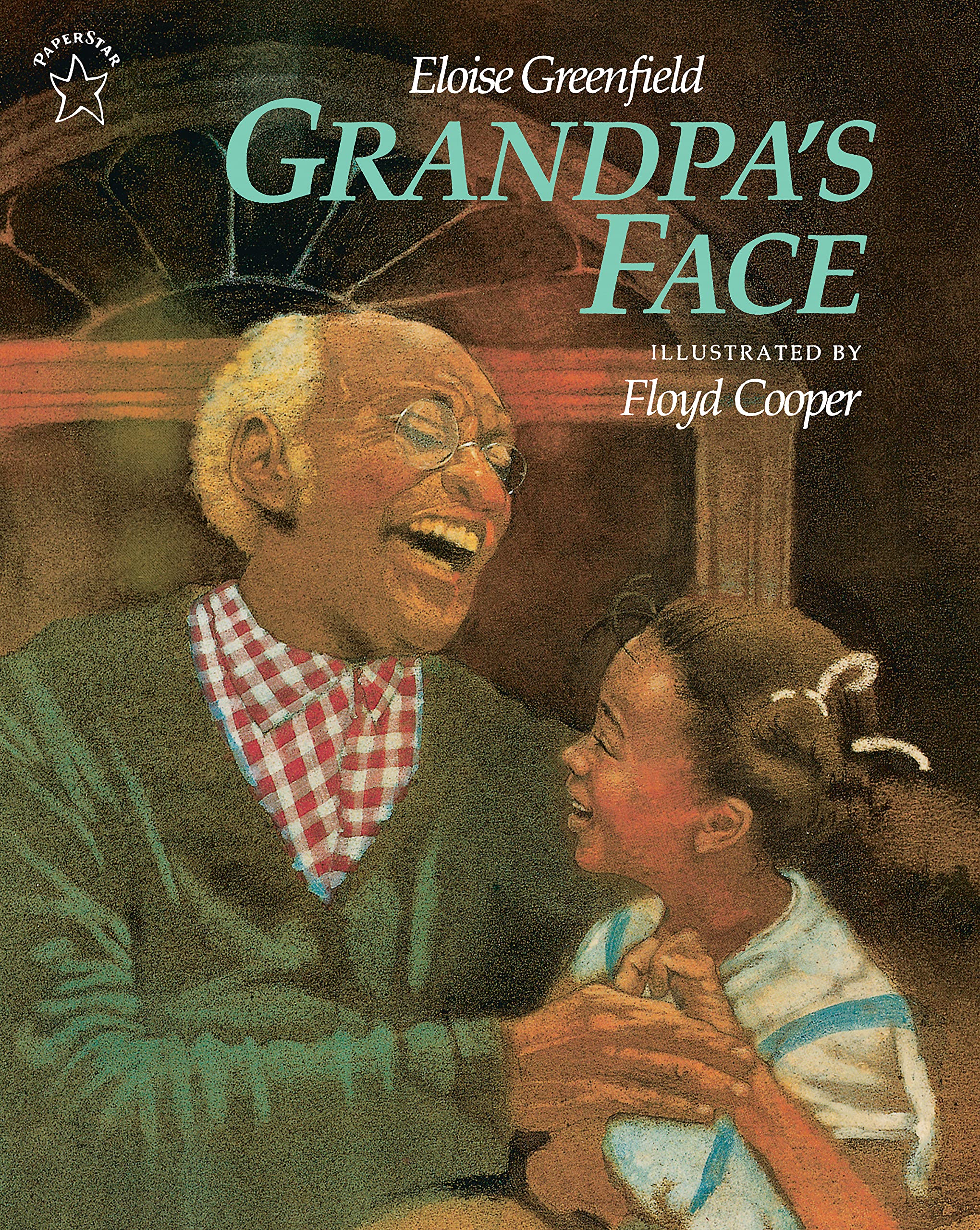

A young, talented Floyd Cooper arrived in my life at a serendipitous time. I was a writer and teacher, but in 1986, in a windfall, I was offered the editor-in-chief position at Philomel Books. Now I had to make books rather than write them. Another windfall? In a stack of manuscripts that had been sent originally to my predecessor, the distinguished editor Ann Beneduce, was one from African American poet and author Eloise Greenfield, a picture book manuscript called Grandpa’s Face. I loved it!

Eloise Greenfield was at the vanguard of children’s literature at that time. There were too few books that told the truth about African Americans, she felt. She was determined to change that. If I wanted to publish Grandpa’s Face, a story about a young hero of color, she wanted an African American artist to illustrate it.

Artists of color like Tom Feelings and Jerry Pinckney had already begun publishing prominently, but, green as grass, I really had no pool of artists to choose from. It was, as I recall, art director Nanette Stevenson who put out the call to agent Libby Ford, who responded that she had a young talented African American artist whose work she wanted us to see.

The artist was Floyd Cooper.

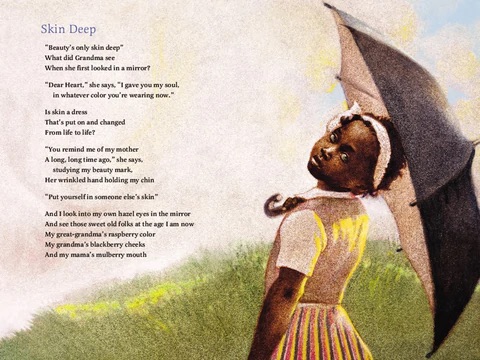

Nanette and I first saw Floyd’s work on the front jacket of a novel. A soft, humming kind of pastel art that was both handsome and uniquely touching. Just right for Grandpa’s Face, where the young boy discovers his own grandfather-actor’s true self. Eloise Greenfield was on board.

The man who walked into our Madison Avenue offices was young—I guessed thirty or so—near six feet, tall by my standards, warm and smiling, and excited for this opportunity to make a picture book. Nanette and I took to him immediately, and about six months later when his finished art for Grandpa’s Face came in on large, oversized artboards, we were not disappointed. Using a medium I had never seen before—drawing by erasing a brown-oil-coated artboard—it was not only the design of the pages that made them so satisfying; Floyd captured the most delicate emotions in his characters. That proved to be one of the most distinctive characteristics of his work: that emotional power. We realized soon enough that his art began with how profoundly Floyd himself felt and saw his subjects. He was no ordinary artist. Maybe no ordinary human being.

In those days, at Putnam-Philomel, the imprints grew stables of authors and illustrators. When editors discovered talent, they were encouraged to sign them up for four, five, or sometimes even six books into the future. Floyd became one of the artists in the Philomel group of artists along with Eric Carle and Ed Young, John Schoenherr, and, soon after I joined Philomel, a bright young talented Patricia Polacco. My challenge, as editor-in-chief, was not only to publish 25 books a year, at least half of them picture books, but to use the unique talents of these artists and authors. To keep them busy—and off of other publishers’ lists!

Like other publishers at this time, I felt strongly it was time for a change. I was determined to publish stories more widely, stories that made a difference in children’s lives. All children’s lives. That contributed to their taking their place in the world and, where the call came, to their getting a fair shake. Maybe because I myself was a parent of three and maybe because I had taught at an alternative high school for ten years where difference was celebrated, I felt this profoundly. Editors and publishers have often felt the responsibility of publishing right, taking the flag of publishing into a kind of front line of contemporary culture. I was just one of a cadre.

I felt a particular responsibility to Floyd. I loved his walking into the office with a stack of finished art. He had that immense warmth, the twinkle in his eye, always the funny remark. There was a temptation to use him mainly for African American stories—certainly, there was the need. And he was a natural to create the art for these stories, but there was a broad humanistic vein in him that was so clear. He seemed to “want” for children across the board. All children. And they could represent many cultures and races. I was determined that he should publish broadly.

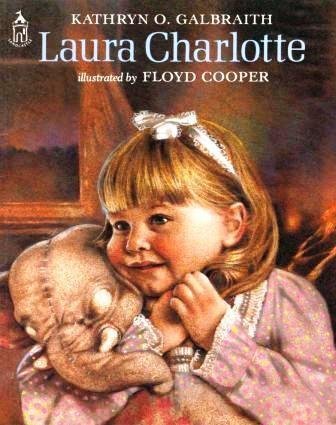

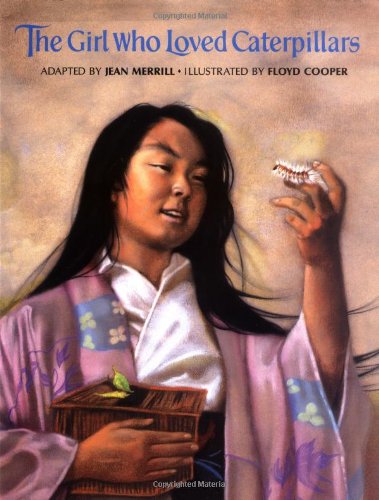

His second book was Laura Charlotte by Kathryn Galbraith, about a white child who shares a history—and a stuffed elephant—with her grandmother. That book, stunningly beautiful, proved to us that he was an artist who could illustrate broadly. The third book was The Girl Who Loved Caterpillars by Jean Merrill, a story about a young Japanese girl who broke the mores for women in a time long before it seemed possible; it touted the strength in girls and women—and the courage to use it.

There was always that push against the mores of the times in Floyd’s books. Not merely to present a story, but a character that pushed the limits of who or what she or he was. A statement of hope. Now becoming a regular in our office, definitely one of our most prominent artists, Floyd illustrated a story by Virginia Fleming called Be Good to Eddie Lee, a story about a Downs Syndrome boy regarded as a drag on two neighborhood children, but who turns out to be the wise and sensitive child of the three, the one who discovers a secret pond of tadpoles when the other two couldn’t. Floyd went back in after his erasure-drawing of this book and applied a delicate watercolor. Some of his paintings when Eddie Lee is looking through the water at the pond’s stony bottom are jewel-like.

Be Good to Eddie Lee remains one of the most sensitive and beautiful books Floyd ever created for Philomel.

This idea of discovering stories for a stable of artists could be a demanding one. Certainly, for me who started out as a writer, not an editor. I really did not have a list of agents knocking on my door, though it helped that Philomel’s John Schoenherr won the Caldecott Medal in 1987. That opened a few doors. But one day, in search of Floyd’s next story, we sat in the conference room—the oversized room where finished art was always laid out on a giant table—and talked about the next book. Always fun, but this time there was no ready manuscript.

I finally said, “Do you have a story you want to illustrate, Floyd?” “Yes,” he said, curious. “I do.” By then I had learned a lot about Floyd, where he grew up, that he was part Native American (Muscogee-Creek), a descendent of people who had walked the Trail of Tears, and part African American. I heard that he had always drawn, that he had a great mentor at Hallmark, Mark English. I also heard that he was dating a beautiful model named Velma and hoped someday I could meet her. He showed me a photograph in a magazine of her modeling, a tall beautiful woman who became his wife.

“Yes,” he said that day, “I’d like to illustrate the story of Langston Hughes.” “Floyd, why don’t you write that story?” I said. “I am not a writer,” he said. I had heard him tell stories ever since his earliest days with Philomel! “Maybe you are,” I told him.

And it turned out that he was. He researched and wrote the story Coming Home, a story of the young life of Langston Hughes. I read the book again recently, and saw once again, that Floyd didn’t merely lay the facts of Hughes’ life out, Floyd discovered the Voice to tell the story. I loved it all over again.

It was at one of those early Langston Hughes talks that Floyd told me something about Lawrence, Kansas where Hughes grew up, how in the mid-1800s William Quantrill and his raiders swept into town, targeting African Americans, killing them, and burning their shops and homes to the ground. This led to Floyd’s telling me that day that a brutal attack also happened in his hometown of Tulsa in the 1900s, in a thriving area of African American doctors, lawyers, bankers, and successful businesses, when a white mob rampaged and burned the place to the ground. Hundreds died. It was 1921. I didn’t know then the area was called the Greenwood District. I know now that his own grandfather was actually there that day, and later when Floyd was just a boy, told him that story. I only learned the name of the place this year when the remarkable book, Unspeakable, written by Carol Weatherford and illustrated by Floyd was published in 2021 on the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre. Editors learn, too.

Once Floyd knew he could write as well as illustrate, he could choose his own stories. He chose a story from Michael Jordan’s life and called the book Jump. The exquisite forms of Michael Jordan, particularly in that famous slam-dunk-jump would challenge any artist, but Floyd took it to its proverbial height, capturing the fluid, lyrical, and famous leaps of one of the greatest basketball players of all time. Floyd wrote and illustrated this book.

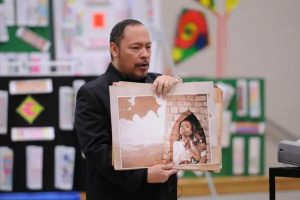

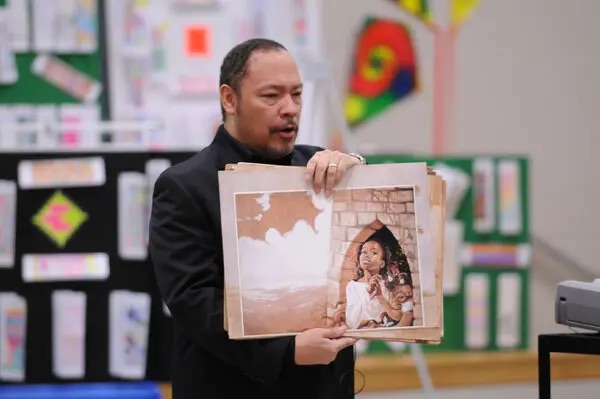

I learned something new about Floyd when we both went to the Highlights Chautauqua Writing for Children conference when he was asked to teach. It may have been his first time. It was 1993, and I was visiting his workshop, a group of artists and writers gathering around him listening, everyone intrigued, when he took out an empty artboard, and, while speaking, coated it, letting it dry. Still talking, joking, confident. Then, as if he was slipping into a song, he started erasing, creating the character on the artboard. The illustration seemed almost magically to emerge.

it was clear to me that day that Floyd was a natural teacher. Warm, talented, witty, but, oh my goodness, confident. It was that confidence that took the audience right into his orbit. Sometime during these years, Floyd Dickman, an Ohio teacher, discovered him as well, how talented he was as a teacher, and toured Floyd in schools all over Ohio for weeks at a time.

He became a regular teacher at the Highlights Foundation workshops where I was on the faculty, too. The Highlights staff put children at the heart of any workshop they run. Floyd very quickly became one of their best teachers, unforgettable. Before Floyd left us, a cabin had been named for him there, featuring all his books and major pieces of art. Writers and artists simply took him to their hearts.

Adding at least one Philomel book annually to his growing list of books, it wasn’t surprising that he would be discovered by other publishers. The first one I remember, published by Harpers, was Brown Honey in Broom Wheat Tea, written by Joyce Carol Thomas, which won a Coretta Scott King Award for Illustration in 1994. The following year he won another illustrator’s award for Meet Denitra Brown by Nikki Grimes. Such good books. I admit it, I envied them. As for Floyd, he was on his way.

This year, with Floyd’s tragic death, I felt as if my son had passed away, but he was more of a lifetime partner. First book he illustrated—together. First book he wrote and illustrated—together. All those meetings in the conference room trying to imagine what next? Floyd taught me as much as I taught him. I counted on his friendship, and I think he counted on mine. Despite not having worked together for years, we remained, in many ways, inseparable. Pals.

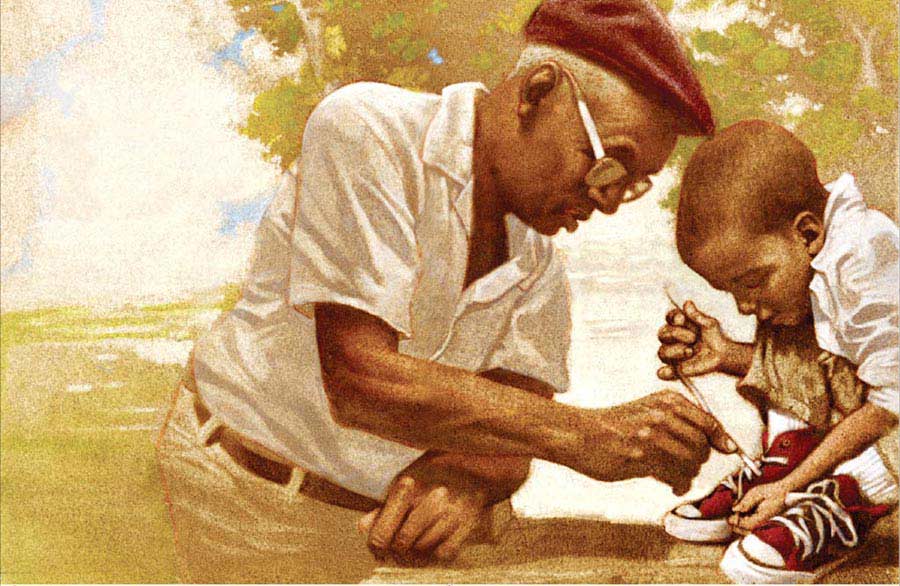

At a virtual memorial service held this year on January 7, the program ended with a recording of Floyd reading his beloved Max and the Tag-along Moon. That book had already had an amazing life. Dollie Parton had selected it for her Imagination Library. But here he was reading it himself on video. It is a beautiful reading about a boy and his grandfather who were going home, the grandfather assuring the boy that the moon would tag along, follow him home. And, of course, it did. The ending assuring the little bedtime boy that just like the moon, his grandfather would always be there for him. I thought of his two grandsons.

Floyd began that reading in his gentle voice. “Max and the Tag-along Moon written by Floyd Cooper. Illustrated by Floyd Cooper.” Then that smile. He’s proud of his work. My heart swelled with pride. At the end of the reading, Floyd hugs the book to his chest.

“I don’t think I can write,” he’d once said. “I think you are a storyteller,” I’d said. And he was. Floyd wrote in his author’s note for Coming Home that Langston Hughes was a beacon for dreamers. “His dreams spawn hope, and from hope springs life….” Floyd wrote. “Hopeless is homeless! And so Langston beckons us home.” As I write this, I think and feel—so does Floyd—in his art and words and witness, he beckons his readers home.

Check out more Guest Q&A‘s with our community!