CBC Diversity 101: Blurring the Lines Between Familiar and Foreign

Part II—A Focus on Dialogue

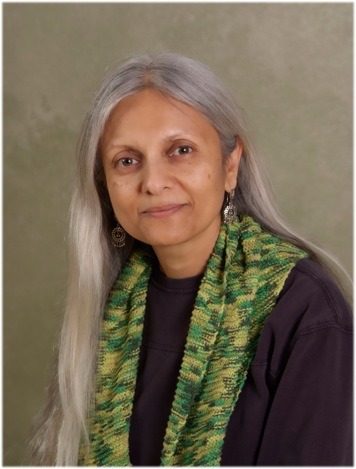

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Uma Krishnaswami

My Personal Connection

The books you read as a child are as real as the places you live in or the people around you. They whisper to you of the possibilities the world can offer, like mental pathways into your own as-yet-unlived future.

In that category, Rumer Godden gave me permission to write. Kipling both enchanted and troubled me; only many years later did I understand my own need to write about the country he depicted with his strange colonial mixture of tenderness and disdain. But as a child of the late 1950s growing up in India, I cut my reading teeth on Enid Blyton.

I learned a lot from Enid about humor, family, friendships, and the pleasure of racing along a swiftly unfolding plot. Now, thinking back, I am pretty sure that I also learned how not to write dialogue.

Stereotypes/Clichés/Tropes/Errors

Consider this passage. The characters, including Kiki the parrot, have arrived in a fictional place called Barira. They’re met by the hotel manager:

‘Ha – what you call him – parrot!’ said the little manager. ‘Pretty Poll, eh?’

‘Wipe your feet,’ said Kiki, much to the man’s surprise. ‘Shut the door!’

The small man was not sure whether to obey or not. ‘Funny bird!’ he said. ‘He is so much clever! He spiks good! Polly, polly!’

‘Polly, put the kettle on,’ said Kiki, and gave a screech that made the man hurry out of the room at once.*

*(US readers, note that the punctuation is correctly quoted from this UK edition)

Note the reference to the speaker as “the little manager.” In the allocation of power, even the talking parrot is higher up than this adult character in a developing country. Note the deliberate errors in his speech, his hesitation in choice of words, his mildly mangled pronunciation and syntax. All of it results in making the foreigner seem an object of ridicule.

From The Valley of Adventure, here’s a passage where the children talk about the natives of the country they’ve landed in:

‘What country are we in?’ said Lucy-Ann. ‘Shall we be able to speak their language?’

‘I don’t suppose so for a minute,’ said Philip. ‘But we’ll just have to try and make ourselves understood.’

One wonders if they pulled it off by shouting or speaking… very… slowly.

This isn’t meant to indict Enid Blyton as a person or as a writer. In Blyton’s 1940s world, speakers of English were “us” and everyone else was “them.” Social psychologists call this “ingroup bias.” We all have some version of it. As writers we need to become aware of our own biases as we create the voices of our characters.

Things I’d Like to See

Here’s what I tell my students in the MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

1) In dialogue, create speech patterns that don’t stereotype. This means listening, really listening, for character voice, a process that is equal parts meditative practice and craft. If you don’t listen closely enough, you end up transcribing real conversation, and we all know the paradox in that—real speech, written down as dialogue, sounds fake. Take that across cultural lines, and those transcriptions sound not only fake but patronizing.

2) Use colloquial speech—please don’t take all the contractions out. Personally, I’m tired of hearing South Asian characters who sound like Gunga Din. When you’re writing contemporary fiction, let your characters sound as if they live in the same century as we do. You’re after cadence, not caricature.

3) When characters use a sprinkling of languages other than English, allow the meaning to emerge through context. Parenthetical translation isn’t incorrect, exactly, but it can become annoying if it’s overused. Sometimes mood matters more than literal definition.

4) It really helps if you have at least a working familiarity with the language you’re trying to sprinkle in. Otherwise your characters are going to sound as if they’re reciting from tourist phrase-books.

5) Get into your characters’ hearts and souls, not just their thoughts. Emotional resonance is what you’re after, regardless of what kind of story you’re writing. Dialogue that is too cerebral will feel flat, as if your characters were talking heads. Then again, make sure that the character’s emotions feel true to his or her cultural context. Oh, and while you’re at it, make sure you’re not stereotyping that context either.

6) Whether you’re writing within or out of your own cultural context, let dialogue do the work it’s meant to do—show subtext, hint at unspoken emotions and interpersonal dynamics, affect the momentum of the story by driving it forward or lingering for a glimpse into something deep.

Suggested Reading

- In This Thing Called the Future by J.L. Powers, Zulu words are used in dialogue with subtlety and sureness. The author is aware of the choices she makes in matters like standardizing plural forms for clarity or employing nouns in sentences.

- Tell Us We’re Home by Marina Budhos. In this novel with a braided structure, the voices of three immigrant girls are perfectly tuned.

- Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and Starry River of the Sky, by Grace Lin. The dialogue in both books seems an effortless extension of the storyteller’s voice.

- The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano by Sonia Manzano integrates Spanish words and phrases into dialogue with ease and fluidity. Each spoken voice is clear and distinct.

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of The Grand Plan to Fix Everything and The Problem With Being Slightly Heroic, both from Atheneum Books for Young Readers.