Industry News

-

Nelvana Partners with Mother Daughter Team Julie Andrews and Emma Walton Hamilton to Develop Very Fairy Princess TV Series

Toronto, Canada – Corus Entertainment’s Nelvana Enterprises, one of the world’s leading international producers and distributors of children’s animated content, is partnering with internationally renowned actress and author Julie Andrews and her …

-

Happy Birthday, Hans Christian Andersen!

Though tall and awkward, Andersen originally dreamed of becoming an actor. He moved to Copenhagen in hopes of performing at the Royal Theater. The directors were less than impressed and …

-

It's My Privilege

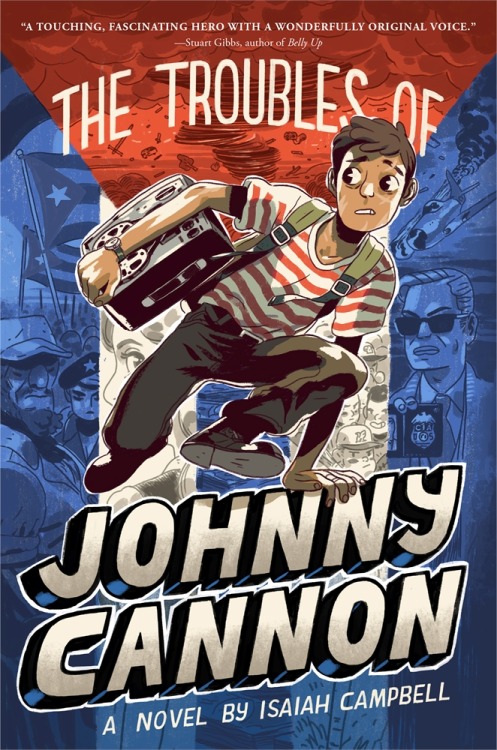

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Isaiah Campbell

“I remember the day that I became colored,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote in How it Feels to be Colored Me. In that essay, she related how she’d never thought much about her own skin color until she turned fourteen and moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where she encountered discrimination that transformed her from “Zora of Orange County” to “the little colored girl.”

I first read that essay when I was in college, and it blew my mind out of my ears and onto the pile of pizza boxes in the corner of my dorm room. I’d never imagined that experience for anyone. What was it like to have your identity redefined into a category you never knew existed? What was it like to go from just being a girl to being “just a girl”? To go from being one of the guys to being “one of those guys”? To realize that, no matter your achievements or accomplishments, people would first notice the color of your skin?

Years later, I would understand that the very fact I’d only just then been exposed to those feelings was, in itself, a similarly defining revelation. Having the freedom to live without such discrimination and restriction is the essence of Privilege, as is being blissfully unaware of what the heck Privilege is and how it affects life (you might recognize that state of being from its proliferation on Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, and Facebook).

When I decided to write The Troubles of Johnny Cannon, I hoped to open the eyes of middle-school readers to the reality I didn’t see until I was an adult. I had been thinking about the “default protagonist” in literature, i.e. the Straight-White-Male character that we often imagine until a rogue character description informs us otherwise. And when that darn character description tells us the character is not straight, or not white, or not male, we expect the story to be about what it’s like to not be the default character.

In other words, Diverse Characters often teach the reader what it’s like to be different, while Straight-White Characters get to go on any adventure they want and happily ignore their own state of being.

And so, like Kristoff when he almost told Olaf what happens to snowmen in summer, I felt compelled to clue the little white guy in on how the world really works.

When Johnny’s story begins, he has it pretty bad. He lives in poverty. He’s in a single parent home. His father is disabled. He doesn’t fit in at school, doesn’t know how to talk to his dream girl, and can’t stay out of trouble to save his life (hence the name of the book, right?). If you told Johnny that he was privileged, he’d laugh in your face. “If I’m privileged,” he’d probably say, “then whoever ain’t privileged is better off dead and buried.”

But everything changes when he is forced to befriend his African American neighbor, Willie Parkins, and realizes there’s a difference between privilege and prosperity.

As a minister’s son with both parents, Willie ought to be better off than Johnny, but he’s not, and it doesn’t make sense. Johnny is as poor as Job’s turkey, but he can go into any place of business even if he can’t afford anything. Johnny has to hunt for his food, but at least the community trusts him with a gun. Johnny gets into fights at school, but when they’re over he doesn’t have to hear about how violent his kind of people are.

The unexplainable disparity between them helps Johnny finally see the world he’s in for what it is. Like it or not, this is a world in which the cards are stacked in favor of Straight-White-Male characters.

And so, in the midst of all his other troubles, Johnny encounters one he can’t fix, and that’s kind of the point. The story isn’t about turning Johnny into a Civil Rights Messiah, swooping in and making the world better for minorities. That would be counterproductive. Instead, the point of the story is to help Johnny, and hopefully the reader, learn empathy. In middle-school.

Empathetic middle-school students. What will the world think of next?

Isaiah Campbell spent eight years coaching students in English before he took his own advice and wrote The Troubles of Johnny Cannon (Simon & Schuster). The second Johnny book, The Struggles of Johnny Cannon, comes out this fall. Go yell at, I mean follow, Isaiah on twitter (@isaiahjc).

-

Apply for the 2015-2016 Children’s Writer-in-Residence Fellowship Program

The fellowship offers an emerging children’s author a $20,000 stipend and an office at the Boston Public Library to complete his or her work of fiction, nonfiction, dramatic writing, or …

-

Dr. Seuss Museum Coming to Springfield, MA

The Amazing World of Dr. Seuss Museum will feature mini-recreations of the Springfield landmarks that inspired Seuss’s stories, and is scheduled to open in June 2016. A second floor, which …

-

The Picture Book Renaissance

The panelists agreed that this age of innovation may be attributed to the expansion of social media channels and the abundance of creative influences…social media has enabled [publishers and agents] …

-

Children’s Art Auction at BEA to Honor Judy Blume

The 21st Annual Children’s Book Art Auction and Reception at this May’s BookExpo America will honor Judy Blume, the pioneering author who helped inspire a new candor in children’s books by daring to write …

-

Happy Birthday, National Ambassador Kate DiCamillo!

Kate was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and raised in Florida. Struggling with frequent illness as a young girl, she immersed herself in books. Her mother and teachers encouraged her early …

-

Heather Has Two Mommies: A Pretty Typical Family

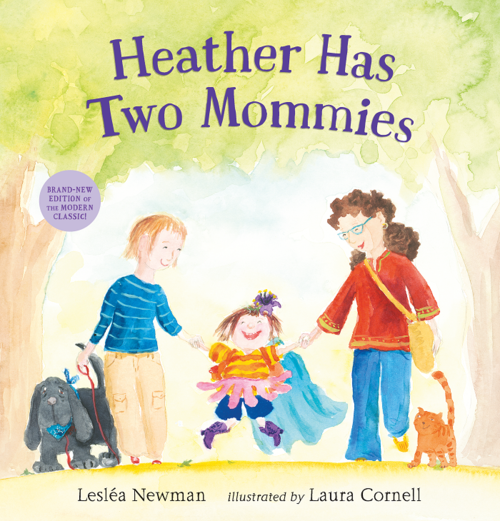

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Lesléa Newman

“So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war,” said Abraham Lincoln when he met Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Those words came back to me in the early 1990’s when I watched a newscast showing Mary Cummins, President of School Board District 24 of Queens NY saying, “This is a war and it will be fought….” Cummins was talking about the Rainbow Curriculum, a resource compiled for New York City school teachers that suggested titles to make classrooms more inclusive and diverse. Cummins objected to three books included in the curriculum that feature families with same-sex parents including my own book, Heather Has Two Mommies. Chaos ensued with protests, demonstrations, and heated school meetings that came close to violence. Headlines such as “How a ‘Rainbow Curriculum’ Turned into Fighting Words” (from the New York Times) and “City writer’s book involved in national gay-rights battle” (from the Daily Hampshire Gazette, my hometown newspaper), gave me pause. Fighting words? Battle? Had I also written a book that started a great war?

That certainly was not my intention.

I wrote Heather Has Two Mommies in 1988 at the request of a lesbian mother who stopped me on the street one day and said, “We have no books to read to our daughter that show a family like ours. Somebody should write one.” I knew exactly how this little girl felt. Growing up in the 1950’s, I had no books that showed a family like mine: a Jewish family celebrating Chanukah and Passover and eating matzo ball soup and challah on Friday nights. After reading book after book about families that decorated Christmas trees and hunted for Easter eggs, I wondered why my family didn’t do those things. Why was my family so different? What was wrong with my family?

No child should feel like there is something “wrong” with her family because her family isn’t part of the dominant culture. Children need books in which they can see themselves in order to feel validated and that they belong.

Heather and her mommies are a pretty typical family. They bake cookies. They go to the park. As the book goes on, Heather attends her first day of school. When the teacher reads a story about a boy whose father is a veterinarian, some of the other children talk about their daddies. Heather wonders if she is the only one who doesn’t have a dad. Heather’s teacher has all the children draw pictures of their families. The drawings make it clear to Heather, her peers, and children reading the book, that families come in all configurations.

Heather’s journey to publication was not easy. After the book was declined by fifty publishers, I was running out of options. One day, I told a friend, Tzivia Gover, a lesbian mom with a desk top publishing business, about my frustration. We decided to publish the book ourselves. We sent out letters asking for $10 donations and raised $4,000. I kicked in some money of my own, we found an illustrator and a printer, and about a year later, 4,000 copies of Heather Has Two Mommies were delivered to my door. About six months after that, Alyson Publications bought the rights to the book and took over. And that’s when all the controversy began.

Many things have happened in the 25 years since Heather Has Two Mommies hit the bookstore and library shelves. The book was listed by the Office of Intellectual Freedom of the American Library Association as the 9th most frequently challenged book to the 1990’s. It has been stolen from library shelves. It has been defecated upon. It has been read into the Congressional Record. But more importantly, it has touched the lives of children.

“Thank you for writing Heather Has Two Mommies. I know that you wrote it just for me,” reads a letter I received from an African American girl named Tasha who saw across racial lines to relate to a white, blonde girl who had two moms just like she did. A lesbian mom told me that her son, Nick, crossed out the word “Heather” every time it appears in the book and wrote his name instead. Nick saw across gender lines and literally inserted himself into the book. Another child with two moms was very nonplussed about the whole thing. After hearing the book, he simply asked his parents, “Can we have a dog and a cat like Heather?”

It is clear to me that children do not come into the world with a preconceived notion of who belongs in a family. As Ms. Molly, Heather’s teacher, says in the book, “The most important thing about a family is that all the people in it love each other.” Children know this. They know it in their hearts and souls. They know it in their bones.

Twenty-five years after publication, a new generation of children with same-sex parents and their friends will have the opportunity to read Heather Has Two Mommies. The book, which has just been released by Candlewick Press, features a shortened text and new illustrations by Laura Cornell which show a family of the 21st century. Heather’s moms are women on the go. And they clearly love their daughter. For example, it is obvious that Heather chose her first-day-of-school clothes all by herself. What parent would dress their child in a yellow-and-orange striped t-shirt, pink twirly skirt, blue shorts, and purple cowgirl boots? By allowing Heather to dress the way she wants, her moms show that they accept her just as she is. And when they drop her off at school, Heather waves to them and joins the other children (a racially diverse group) with a confident smile on her face.

Heather’s family is just one type of family that makes up the wonderful spectrum of human experience. I hope both children who come from families similar to Heather’s and children who come from other types of families will embrace Heather and her two mommies for many years to come.

Lesléa Newman is the author of 65 books for readers of all ages, many of which feature families with same-sex parents including Donovan’s Big Day; Mommy, Mama, and Me; Daddy, Papa, and Me; Felicia’s Favorite Story; and Heather Has Two Mommies. She is also the author of the teen novel-in-verse, October Mourning: A Song For Matthew Shepard which received an American Library Association Stonewall Honor.

-

Categorizing the Human Condition – Re-defining Who We Think We Are

One of the most frustrating arguments I see made so often in the ongoing diversity dialogue is an expressed concern by publishing professionals (in various departments) that books spotlighting diverse characters (whether racial diversity, sexual diversity, or gender diversity, on book covers or as lead characters) will naturally have an ingrained niche appeal, and won’t be as accessible to the broadest reader.

To that I say:

“Why do we expect so little from the average consumer?”

“Why do we assume that the natural response from adults who don’t share a commonality with a diverse character in any respect aren’t hungry to expand their horizons a bit through their nighttime reading?”

Maybe I’m too much of an optimist.

Let’s back it up for a second. Personal share time.

When I was in college at Cornell, I joined a faith-based organization (part of that whole figuring out who I was thing) where out of 150+ members; I was one of two Caucasian members. 99.9% of the organization was composed of Asian American students. One of my suitemates in college dragged me with her to the first meeting for company, honestly not having any idea of this particular cultural makeup to the group.

I still vividly remember walking into the room for the very first time and feeling something I have never felt before – like I stood out. And not in a way that was in any way self-conscious or nerve-wracking, but in a way that was very, very aware of how I was different. There was a sort of initial discomfort that took hold that quickly settled into a sort of unique-feeling self-confidence I hadn’t experienced before. I was experiencing I think, for the first time, what it felt like to be in a situation as a naturally shy person where I couldn’t hide in the crowd; where I might be remembered in this setting with any opinions or thoughts I might share…and it was liberating.

I mention this only because it was one of the earliest examples of life putting me in a situation that is so very rare as a person not classified as traditionally diverse. My viewpoint was shifted in a wonderful way, putting my voice in a different context, while at the same time opening up my own receptive experience to others who offered me different perspectives on a common transitional experience of faith in college. The friendships I made with particular individuals at that organization continue to be some of the most valuable connections I have in my adulthood.

In a broader sense, I share this to connect back to the important point within the diversity conversation that at our core, as humans, it is so, so important to value and tend to our basic, fundamental need to expand our horizons and force open our too-often closed views of the world. This applies to those of every facet of the diversity spectrum – all of us, in every part of the world, and every type of reader and consumer. So much conversation is had about why diverse books matter to those who are of the specified group discussed but, to me, what we need to also consider is how much these books and the opportunities they present to us matter to all of us in the ongoing emotional education of developing who we are as a society.

Speaking for myself, a quiet Cornhusker from Omaha, Nebraska, I could easily have stayed in my little corner of the world after high school. But…

I joined the publishing industry for a reason.

I came to New York City for a reason.

I kept returning to that organization in college for a reason.

I read books regularly from a variety of different authors about different subjects and different cultures for a reason.

I want my life and who I am and how I think to be colored by the full human experience. That experience won’t ever innately be represented solely by my upper middle class upbringing if I don’t immerse myself in worlds outside of my own.

Yes, of course there are those out there who don’t actively look to read or learn beyond what they know – and they’re the worse for it. But isn’t a major purpose of the creative output of literature to provide us all with worlds and people who we can’t find in our daily commute?

So to me, the assumption that the general reader won’t embrace culturally diverse stories is a knee-jerk, unambitious, and pessimistic viewpoint. I believe our society is capable of so much more if we simply push harder within our industry, which is so focused on expanding cultural currency through literature. And there are so many talented authors with so many interesting, diverse stories ready to do just that.

And I’m not ready to give up on us just yet.

-

Happy Birthday, Randolph Caldecott!

Caldecott moved to London in 1872 to work as a freelance illustrator. By 1878, he was an internationally respected picture book illustrator. Today Caldecott is widely considered the father of …

-

Celebrating the Late Walter Dean Myers

Authors Avi, Jason Reynolds, Emily Raboteau, Jacqueline Woodson, Wah-Ming Chang, and Brian Selznick; and performers Justin Hicks, Eisa Davis, Jomama Jones, and Helga Davismany, shared personal reflections and original pieces …

-

Harry Potter Alliance Follows Up Chocolate Win With International Book Drive

Coming off of a landmark victory in successfully compelling Warner Bros. to make all their Harry Potter chocolates UTZ. or Fair Trade, the Harry Potter Alliance (HPA) is running another …

-

First Book and Unbound Concepts Team Up to Help Educators in Low-Income Communities Discover Best Books for the Kids They Serve

BALTIMORE, MD – Baltimore-based Unbound Concepts and the nonprofit First Book today announced a partnership that will help match students from low-income families with high-quality books best-suited for their reading abilities and …

-

Literary Apps for Young Readers

While Bird sees a current decline in the production of children’s book apps, she has come across several “hits” worth sharing: The Barefoot Books World Atlas by Nick Crane Don’t Let …

-

National Ambassador Kate DiCamillo's Advice to Writers

Now an established author, DiCamillo encourages aspiring writers to stop talking and start writing: People come up to me and (ask advice) and the thing that resonates with me about …

-

Remembering Author Terry Pratchett

Pratchett was the author of over 70 books, including such books for young readers as Dodger and Dragons at Crumbling Castle. He also collaborated with close friend Neil Gaiman on Good Omens. Pratchett was knighted for “services to literature” in …

-

The Alan Review | Winter 2015

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Wendy J. Glenn

In the Fall 2014 issue of The ALAN Review, the peer-reviewed journal of the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of NCTE (ALAN), contributors were invited to share their experiences, challenges, hesitations, and successes in using or promoting young adult literature that features characters and/or authors of color.

Statistics suggest that, by 2019, approximately 49% of students enrolled in U.S. public schools will be Latina/o, Black, Asian/Pacific Island, or American Indian (Hussar & Bailey, 2011). However, the field has been increasingly criticized for not reflecting these demographics in the literature published for young adult readers. For readers of color, this can result in a sense of disconnect between lived reality and what is described on the page. For readers from the dominant culture, this can result in a limited perception of reality and affirmation of a singular way of knowing and doing and being. For all readers, exposure to a variety of ethnically unfamiliar literature can encourage critical reading of text and world, recognition of the limitations of depending upon mainstream depictions of people and their experiences, and the building of background knowledge and expansion of worldview.

Consider the experiences of the late Walter Dean Myers: “All the authors I studied, all the historical figures, with the exception of George Washington Carver, and all those figures I looked upon as having importance were white men. I didn’t mind that they were men, or even white men. What I did mind was that being white seemed to play so important a part in the assigning of values” (Bad Boy: A Memoir). And ponder Jacqueline Woodson’s words, “Someday somebody’s going to come along and knock this old fence down” (The Other Side).

The current issue of The ALAN Review addresses what educators and librarians have done (or might do) to give that fence a nudge.

Wendy J. Glenn is Associate Professor in the Neag School of Education where she teaches courses in the theories and methods of teaching literature, writing, and language. She is the former President of the Assembly on Literature for Adolescents of the National Council of Teachers of English (ALAN) and current Senior Editor of the organization’s peer-review journal, The ALAN Review.

-

Getting It Right

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Peggy Kern

The first time I met Miracle (not her real name), she arrived in a full suit of armor: a thick mask of makeup, black eyeliner pointed like arrows at the edge of her eyes - a warning, perhaps, to not look at her the wrong way - hair slicked back into a severe ponytail, a jean skirt and flat black leather boots suitable for running away, if need be.

My friend, a detective with the NYPD at the time, had arranged the meeting. Miracle was known to police as a reliable source of information about sex traffickers in Brooklyn. She is also a survivor of child prostitution.

When I decided to write Little Peach, I knew I could not attempt the story without speaking directly with victims. I felt I had no right to type a single word on the page without doing so. Little Peach could not be my sheltered imagining of the issue, but an accurate account guided by the victims themselves. My job was to cede my voice, and give rise to theirs.

The first night we met, Miracle and I spoke for three hours.

She told me about the scouts that lie in wait at bus terminals and outside of group homes, looking for runaways and desperate, injured kids. She told me I could go to Port Authority that very night and I would see men wearing red or blue – signifying their particular gang affiliation – hunting for girls.

She showed me the tattoos she was given by her pimp, including a five-point red star placed strategically behind her ear by a sect of the Bloods that deals in trafficking. The placement is intentional: she could easily be identified as their property with the turn of her head.

She explained to me how traffickers use drugs to hook young girls. She herself was hooked on crack-cocaine by the age of twelve. She told me they target black and Latino runaways because, and I quote, “Somebody’s always lookin’ for the white girl, or she’ll want to go home. And that makes her a risk.”

She talked about her mom, who was a prostitute and addict, and the sexual abuses she endured at the hands of mother’s “customers.”

She taught me the difference between the young girls who are sold online and kept out of sight in hotels, and the older ones who are put out to pasture on the “track” – a term for the largely unpatrolled street corners where women are sold.

She told me about the girls she’s loved like sisters through the years. Some of them were murdered. Some were sold to other pimps. Most simply disappeared into the prison system or the streets.

She could not talk about her foster father, who had abused her so badly she still, all these years later, had no words to describe it.

She cried. So did I. And she said, “No one ever asked me these questions before.”

The second time we met, Miracle arrived in a comfy sweat suit. No makeup, hair down. Soft eyes. Sneakers. She continued to talk. And I listened to every word she said.

My time with Miracle, and with another woman named Jen, who I met on the “track” on Flatlands Avenue in Brooklyn and whose story was unbelievably similar to Miracle’s down to a tattoo on her chest, informed the voices of Michelle, Kat and Baby – not just culturally, racially, and socio-economically – but emotionally. There are moments in the book when Michelle can barely speak to you. Her sentences are broken. She almost loses her ability to communicate because what’s happening is so intolerable. It’s like she’s whispering, or turning her head away. That is the voice of Miracle, in many ways. And of Jen. And of the other girls I watched in the hotels of Brooklyn, but could not get near.

Miracle also taught me the geography of Little Peach. I depicted her world as best I could, and the world shown to me by my friend with the NYPD. Pink Houses, Coney Island (where Miracle and I would meet), even North Philadelphia, where I spent time working with students years ago – those locations are as real as the girls Peach represents.

Over and over, as I was writing the novel, I would ask myself: Would Miracle agree? Would Jen? If they read this, would they nod their heads and say, Yeah. That’s right, Peg. That’s how it went down.

Research is important, no matter what you’re writing about. But for Little Peach, it meant the difference between my sheltered imagining of what sex trafficking is like – and the actual accounts of victims.

The obvious truth is that no matter how much time I spent in Brooklyn, no matter how many conversations I had with survivors, I will always be a white woman. And I always got to return home to my apartment at the end of the night, where I sleep in safety, where I have food in my refrigerator and where my blond daughter lives in privilege compared to so many other girls in this country.

That I cannot change. And yet, the story matters so much. Peach matters so much. And so, you try. As a writer, as a human, you try – with all your powers and heart and inescapable limitations – to accurately depict the children you are bearing witness to.

You do your best to get it right. And if you missed the mark in moments, you own that, too.

But silence is not an option. Silence – when kids are literally dying – is unacceptable.

Peggy Kern has written two books for the Bluford series. She lives with her daughter in Massachusetts.

-

Audible to Produce Direct-to-Audiobook Stories

Fantasy writer Philip Pullman is one of many writers (from TV, film, and literature) to participate in the new audio storytelling project: I love this…We are taking part in a …